“Sweep away the inconvenient past and imagine the future made real.”

Cities are contested spaces. With their great flows of capital and humanity, with dense, impacted layers of history, shifting alliances and conflicts between competing power centres, with all of the energy and potential of so many people gathered in one place, cities can be the arenas for our greatest triumphs or most abysmal failures. Sometimes, renewing a city can feel like rebuilding an aeroplane in mid-flight. The lure of starting anew is always strong. To sweep away the inconvenient past and imagine the future made real.

Twenty-five kilometres west of Melbourne’s old colonial heart, 775 hectares of state-owned paddock and old research labs in Werribee has been earmarked for total transformation by a consortium of developers. In November 2015, the Metropolitan Planning Authority selected the Australian Education City (AEC) proposal, as the preferred bidder for the old State Research Farm. The AEC plan was far grander in scope than anything envisaged by the state planners: a new city on the old city’s far western fringe, a development hub on a massive greenfield site in the middle of the corridor where Melbourne’s future population growth would flow.

Ross Martiensen, Executive Director with Australian Education City, says the opportunities in a new planned community on a greenfield site spring from the absence of legacy infrastructure and the freedom “to layer the new networks and sensors from the ground up to provide optimum coverage and performance. Older urban centres are also less attractive to developers because of political and economic barriers to building out that infrastructure.”

Demographer Bernard Salt has described Melbourne’s west as “this nation’s last untamed urban frontier”. In its first two centuries the city expanded into the soft loamy soils of the farms and market gardens in the east, but that space has all been consumed. Melbourne is the only major capital that can offer the prospect of an open range. “Perth isn’t going to push east,” Salt writes. “Brisbane will not reach out to Toowoomba. Sydney cannot push east.”

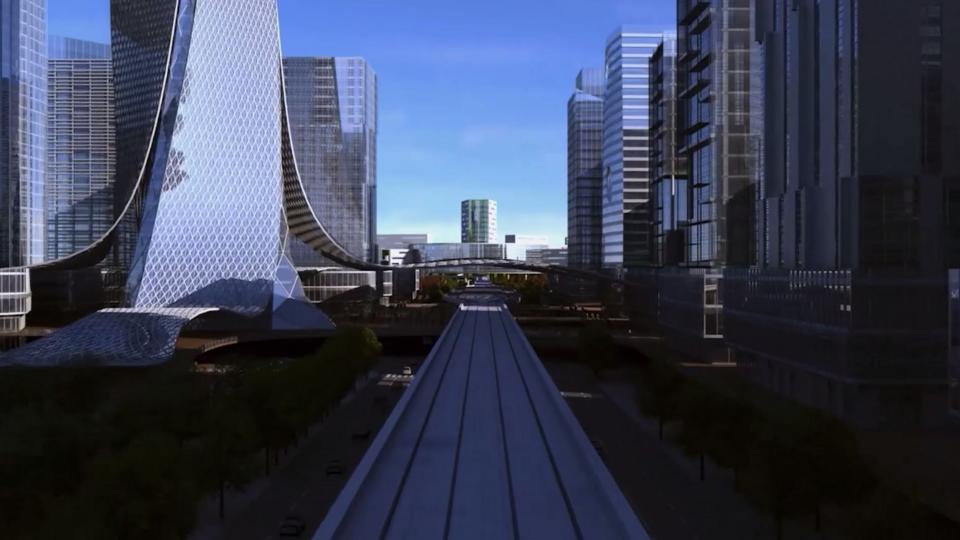

The ambition behind the plans for the Australian Education City goes far beyond the usual developer dream of running up a few acres of tract housing and a shopping mall. Large new campuses are planned, with the involvement of the old sandstone universities and sister institutions from China, with its enormous appetite for spending big on western education. A city of 100,000 residents, many of them staff and students of the new campuses, will arise in fifty-storey towers if the mooted plans go ahead.

CLICK TO PLAY VIDEO

And because they’re working with a greenfield site, the developers can plan for a sophisticated and fully networked urban environment. Bud Kapoor, Sales Manager for Smart+Connected Communities at Cisco, says the plans for Werribee represent a new way of looking at developing cities. As an example of the complexity of dealing with so-called brownfield sites, older cities might have to maintain a dozen different types of urban lighting. Working with a clean slate somewhere like Werribee, however, developers can specify a simple, coherent street lighting solution throughout the area. They can also monitor and manage the system with much greater control.

Distributed sensors would gather huge troves of data for analysis and action, or what Cisco calls activation. “It is a very unique vision,” says Mr Kapoor. “They’re not just building a residential suburb. They’re not just selling houses or apartments. They’re building and curating a whole city.”

He cites the example of a client, a mayor from another city, who decided to test out his own transport system by catching the bus to work one day. The bus arrived three hours late and the mayor gained a much-improved understanding of the frustrations facing his residents and commuters. The problem was not necessarily the missing transport, but the missing information. As a commuter, he didn’t need to know why the bus wasn’t coming — just knowing he needed to make alternative arrangements would have been enough.

The resident of a fully networked city, comprehensively covered by sensor suites, need never live in the dark. They can plug directly into the data flows to make informed decisions. Cisco offered advice to the Australian Education City about more than the digital architecture needed for a future city of 100,000. They looked at the proposal, with its heavy emphasis on building everything around a world class educational institution, and also provided guidance on what that particular urban setting would require.

It is not a specifically Australian approach. Mr Kapoor says that many Cisco customers, even in older cities, have seen the power of opening up their data. In London, for instance, the city opened up its transport data, letting outside developers write applications to offer commuters and businesses easy to use sources of transport information.

Security, which might seem a challenge in open systems, is less problematic than you might first imagine. Cisco builds for customers in the national security sector, and lessons from securing that infrastructure can be applied to the needs of civic governance. Australian Education City’s Ross Martiensen says the Smart City infrastructure will create a fast efficient platform for communication “but the individual corporates and users of the platform will have their own encryption and security measures. As for the sensor data collected by the network, this is a regulatory discussion that would need to include data owners, stakeholders and Government to provide the right protection for individuals.”

If and when the dream for Werribee is realised, the greatest change from what went before probably won’t be in the soaring lines of the residential towers and campus buildings. Rather, it will be in the wealth of information flowing from the sensors embedded within them and across the entire city.